First of Five Parts

Part One: The Power of the Anglosphere

It’s paradoxical that American soft power—that is, our political and cultural influence around the world—seems never to have been greater, and yet at the same time, America itself seems to be fissured. That is, our politics riven and our population polarized. Over time, this fissuring is assuredly problematic, not only for the sake of our beloved republic, but also for the sake of the free world coalition, which is under dire threat in Ukraine, and, also, to a lesser extent, in Taiwan.

“Soft power,” of course, is a concept coined by Harvard’s Kennedy School academic, Joseph Nye. He first used the term in his 1990 book, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power, and then elaborated on it in his 2004 book, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. As he wrote,

Everyone is familiar with hard power. We know that military and economic might often get others to change their position. Hard power can rest on inducements (“carrots”) or threats (“sticks”). But sometimes you can get the outcomes you want without tangible threats or payoffs.

Applying the same carrot/stick concept to nations, Nye continued,

A country may obtain the outcomes it wants in world politics because other countries—admiring its values, emulating its example, aspiring to its level of prosperity and openness—want to follow it. In this sense, it is also important to set the agenda and attract others in world politics, and not only to force them to change by threatening military force or economic sanctions. This soft power—getting others to want the outcomes that you want—co-opts people rather than coerces them. Soft power rests on the ability to shape the preferences of others.

Shaping the preferences of others, for better or worse, is exactly what the U.S. does best. We might consider: Just in the past decade, such distinctly American concepts as Occupy Wall Street, #MeToo, the Green New Deal, and Black Lives Matter have resonated around the world. In 2020, for instance, Keir Starmer, the leader of the British Labour Party, took a knee. Starmer might well be a future prime minister of the United Kingdom; and yet he’s been imitating the gestures of an American football player. We can add that the Dobbs case, reversing Roe v. Wade, was the subject of worldwide commentary, including from heads of state.

Indeed, American memes are so strong that they even regularly infect adversaries; in March 2022, Russian autocrat Vladimir Putin railed against "cancel culture." (Strange to think that Moscow was once a master of meme-generation, streaming out to the Communist International, but that was then; now, the Russians grope for our memes.)

Part of American meme-mastery, of course, is American social media. We can ask: Is there any important country in the world that does not have a Twitter account? Is there anyone in the world who does not know about Donald Trump? The yellow hair? The red tie? MAGA?

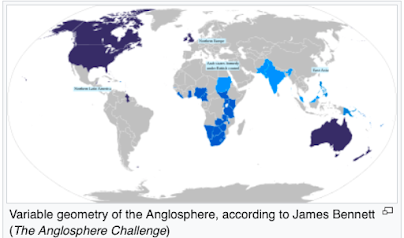

This is all part of the Anglosphere, the quasi-geopolitical notion that the world’s English-speaking peoples are destined for some sort of political unity, as well as cultural unity. In fact, some 1.5 billion people around the world speak English—that’s about a fifth of the world’s population. However, among the elite, the chattering classes, the percentage of English speakers is surely far higher. So it was that the American journalist Ben Smith could declare that his forthcoming publication, Semafor, will target these English speakers, wherever they are on the planet. “There are 200 million people who are college educated, who read in English, but who no one is really treating like an audience, but who talk to each other and talk to us,” he said. “That’s who we see as our audience.”

Yet the soft power of the Anglosphere is more than just the hegemony of the English language. It’s also the appeal of the Anglo-Saxon idea—or, if one prefers, the liberal idea— of freedom of speech. One needn’t argue that Francis Fukuyama was right about the worldwide “End of History” to nonetheless concede that he was right about the preference of many people.

For many—and by many, I mean billions—this endless give and take that comes with freedom is what makes American debates, cultural as well as political, so exciting. In the most literal sense, you don’t know what’s going to happen next, because there’s no controller and no censor. Whatever comes spewing out of American media, including social media, is whatever people are thinking. And if much if it is unappetizing, there’s always some of it that is appetizing, and there’s always much of it that is compelling.

So we might be reminded of what Thomas Jefferson wrote from Paris in the 1780s: If he was faced with a choice of “a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” This endless contention of media not only makes for interesting news consumption (even if it takes some effort to smelt away the dross) it also makes for better governance, as a free press checks and balances the state. This point made by Jefferson, our first secretary of state, was well articulated by the 71st secretary of state, Antony Blinken. On March 18, 2021, in an impromptu debate with the Chinese foreign minister, Wang Yi, Blinken declared

. . . there’s one more hallmark of our leadership here at home and that’s a constant quest to as we say, form a more perfect union. And that quest, by definition, acknowledges our imperfections, acknowledges that we’re not perfect. We make mistakes. We have reversals, we take steps back. But what we’ve done throughout our history is to confront those challenges, openly, publicly, transparently. Not trying to ignore them. Not trying to pretend they don’t exist. Not trying to sweep them under the rug. And sometimes it’s painful. Sometimes it’s ugly. But each and every time we’ve come out stronger, better, more united, as a country.

Fact check: True. At least for most of U.S. history. Yet today, many argue that “disinformation” is such a threat that something must be done, such as Sovietly named—and mercifully short-lived—Disinformation Governance Board. Yet whatever the U.S. government does, or doesn’t do, about “disinformation,” there are easily a hundred, if not a thousand, non-profits, all monitoring, analyzing, and warning against “disinformation.” Of course, as a reminder of the power of the Anglosphere, one can go to the internet and google (two more agents of the Anglosphere) and read all about it.

Of course, a Google search for “civil war” and associated concepts will yield up a gazillion hits. And it’s hard not to agree with at least some of the concerns about the future of our union. As I wrote in March for The American Conservative, “The United States has all the preconditions for a civil war today except one: the willingness to actually fight for the sake of disunity.” I still think that’s true, even if I’m a little less sure about the unwillingness to actually fight.

So this is the dilemma of American power: Around the world, the Anglosphere is robust, and yet here at home, America is deeply divided. So can this divided house still stand?

This question is likely to be sharpened if America continues to show success in Ukraine. As of mid-August, it seems that Western military aid is so enhancing the courage of the Ukrainian armed forces that it’s possible, maybe probable, that Ukraine will fight Russia to some kind of draw. A Korean-style stalemate seems likely—and given the early expectations of a swift Russian victory, that’s a comparatively positive outcome. To be sure, it’s tragic to think that Russia will hold on to a single acre of Ukrainian territory, and yet the good news is that Ukraine is now firmly anchored in the West. At this rate, it will soon be obsolete to speak of Russia’s implied dominion over Ukraine, just as it is anachronistic to speak of Japan’s dominion over Manchuria, or of Britain’s dominion over Palestine.

So that’s the good news: The perimeter of the Free World has been expanded, with Ukraine firmly within the perimeter. As has long been the case, the perimeter of freedom is mostly safeguarded by the hard power the American military, bolstered and amplified by American soft power.

Yet the bad news is the aforementioned weakness at home. The fierce debate over the legal issues surrounding Donald Trump are likely enough to resolve themselves soon enough—the American legal system may move slowly, but it grinds hard—and yet the deeper conflicts of geography and demography are likely to remain, and that could undercut our hard power, and maybe even our soft power. As I argued in that March piece, red vs. blue could be the new Austria and Hungary.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. My only point now, in part one of this four-part series, is to emphasize the strangeness of our situation: Our soft power abroad is manifest, and yet our soft underbelly at home is obvious. So it’s useful to explore how past realms managed their soft power.

Next in Part Two: How the Romans wielded soft power.

(Picture credit: Wikipedia)

No comments:

Post a Comment